Christians, unfamiliar with post-biblical Jewish religion and the cultural circumstances of first-century Palestine, often entertain an entirely false concept of Jesus’ understanding of God and his relation to him. They assume that the contemporaries of Jesus felt distant from God and did not perceive or address him as their Father and the Father of all other creatures. They have also an erroneous appreciation of what the term ‘son of God’ signified in those days. A well-known New Testament scholar goes so far as to declare that the invocation of God as Father was ‘unthinkable’ (my italics) in the prayer language of the Jews of Jesus’ age (Ferdinand Hahn, The Titles of Jesus in Christology, 1969, p. 307).

To clarify these issues, one must first focus on the notion of the fatherhood of God in general, and, more precisely, on how God is envisaged in the Gospels as the Father of Jesus and of his followers. The frequency and variety of the phrases used by the evangelists – ‘my Father’ or ‘your Father’ (spoken by Jesus or his disciples), and even the all-inclusive ‘our Father’ – suggest that this nomenclature, together with the vocative use, ‘Father!’, was in no way peculiar and surprising. On the contrary, the terminology appears to have been common.

As a matter of fact, anyone familiar with Scripture and post-biblical Jewish writings will know that describing God or appealing to him as ‘Father’ is attested from the earliest times down to the rabbinic era. The personal names in the Bible such as Abi-el (‘God is my Father’), Eli-ab (‘My God is Father’), Abi-jah (‘My Father is Yah [the Lord]’, Yeho-ab or Jo-ab (‘Yeho [the Lord] is Father’) witness from the start a familiarity with the theological concept of divine paternity, and from the exilic period (mid-sixth century BC) the idea is positively formulated. ‘For you are our Father, though Abraham does not know us and Israel does not acknowledge us; you, O Lord, are our Father’ (Isa. 63:16; see Isa. 64:8; Ps 89:26; 1 Chron. 29:10).

God is spoken of or addressed as ‘Father’ in the Apocrypha too: ‘O Lord, Father and Master of my life, do not abandon me . . .’ (Ecclus 23:1; see also 4:10; 23:4; 51:10; Tobit 13:4; Wisd. 14:3, etc.). The same is true of the Pseudepigrapha: ‘May the Lord God be a Father to you, and may you be the first-born son and a people always’ (Jub. 19:29; see also 1:25, 28; Test. of Judah 17:2; 24:2; etc.). Similarly, the Dead Sea Scrolls on various occasions employ the same language: ‘My Father and my God, do not abandon me to the hands of the nations’ (4Q372 1, 16), and again, ‘For you are a Father to the sons of your truth’ (1QH 17:35; see also 4Q200 6, 9–10; 4Q502 39, 3; 4Q511 27, 1, etc.).

It goes without saying that in the liturgical language of the public prayer of the Temple and the synagogue, God was usually addressed formally as ‘Lord’, ‘our God’ or ‘King of the Universe’, but one must not overlook the famous supplication, Avinu, Malkenu (‘Our Father, our King’), a traditional formula associated with Rabbi Akiva already in the early second century AD (bTaan. 25b), and the even more apposite ‘our Father who are in heaven’ (‘Avinu she-ba-shamayim’), a customary invocation in rabbinic literature.

Some further early synagogue prayers, too, are directed towards the divine Father: ‘Lead us back, our Father, to your Torah . . . Forgive us, our Father, for we have sinned’ (Eighteen Benedictions 5–6, Palestinian version) and the Aramaic prayer the addish also mentions ‘the Father who is in heaven’. The ancient Hasidim spent a long period in concentration before directing their prayer towards ‘their Father in heaven’ (mBer. 5:1). The Galilean Hanina ben Dosa is the outstanding example of this. In brief, it can safely be concluded that calling on God as Father was traditional in Jewish circles; it was not, as has been repeatedly claimed by illinformed or biased New Testament interpreters, an innovation introduced and practised by Jesus, and handed down only in the circle of his followers.

Arguing this view from a different stance, the renowned German New Testament scholar Joachim Jeremias propounded the thesis that the formula carried a peculiar nuance that linked it exclusively to Jesus (The Prayers of Jesus, 1977, pp. 57–65). According to Jeremias, the Aramaic word ’abba was originally an exclamatory form derived from the babbling of children (’ab-ba like da-da, pa-pa, and ’im-ma like ma-ma). Although addressing God in children’s language would have struck conventional Jews as disrespectful, Jesus, conscious according to Jeremias of his unique closeness to the Deity, was brave enough to adopt the puerile ’abba locution. While Jeremias’s odd theory was promptly shown to be misconceived (see G. Vermes, Jesus and the World of Judaism, 1983, pp. 41–2; and especially and most powerfully, James Barr, ‘Abba isn’t Daddy’, 1988), nevertheless it continues to be repeated, most recently by Pope Benedict XVI (Jesus of Nazareth, 2011, pp. 161–2), despite the fact that it is philologically groundless and from the literary-historical point of view erroneous. ’Abba is not restricted to children’s speech, but appears also in solemn, religious language (e.g. an oath taken on the life of ’abba). Moreover, the New Testament indicates no awareness of anything being extra ordinary in Jesus’ use. For instance, the Aramaic term is never rendered in Greek as papas or pappas (‘Dad’ or ‘Daddy’) but is every time formally translated as ‘(the) Father’ (ho Pater), once as an invocation spoken by Jesus (Mk 14:36) and twice as a prayer formula used by the Christian communities in the Pauline churches (Gal. 4:6; Rom. 8:15).

The best Aramaic illustration of the twofold significance of ’abba is found in the earlier quoted Talmudic anecdote about Abba Hanan. Accosted by boys in the street during a period of drought with the request, ‘Abba, Abba, give us rain!’ the charismatic miracle-worker implored God to listen to the prayer of these children even though they addressed it to the wrong person, being unable to distinguish ‘between the ’Abba [God] who gives rain and the other ’Abba [Hanan] who does not’ (bTaan. 23b).

The double conclusion one may draw from the foregoing observations is that for Jesus, the almighty Lord of the Creation, the Ruler of the Kingdom of God, was first and foremost a provident and loving Father, and that his disciples too were instructed to adopt the same filial attitude towards their common heavenly Abba. The non- mention of natural catastrophes and of the suffering innocents is typical of Jesus’ optimistic outlook regarding the end time. He believed that at the last moment paternal love would eliminate all the miseries of the world and God would be recognized by all as Father. We have to wait until the third century and the great theologian Origen for a firm formulation of this idea (see Chapter 9, p. 222).

As a negative confirmation of the association of Jesus’ attitude to God and the address ‘Father’ it should be pointed out that on the only occasion when his trust appears to have been shaken, namely when the crucified Jesus realized that God was not going to intervene and save him, the invocation Abba is replaced by the less filial ‘my God’, Eloi, Eloi (or Eli, Eli in the Aramaic version of the opening verse of Psalm 22): ‘ “Eloi, eloi, lema sabachtani?” Which means, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” ’ (Mk 15:34; Mt. 27:46). Less heartrending is the pious prayer of Luke’s dying Jesus, ‘Father, into your hands I commit my spirit’ (Lk. 23:46).

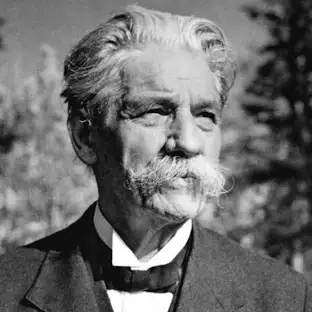

Geza Vermes Christian Beginnings from Nazareth to Nicea, AD 20-235