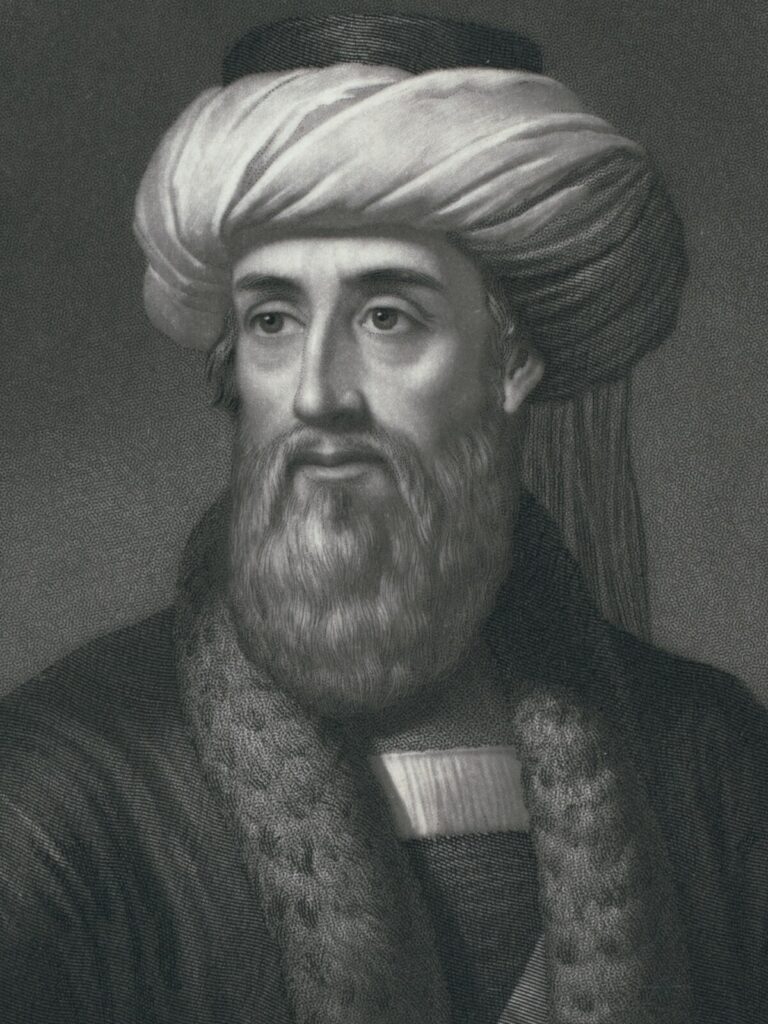

When we look for statements about Jesus from noncanonical writings of the 1st or 2d century A.D., we are at first disappointed by the lack of references. We have to remember that Jews and pagans of this period, if they were at all aware of a new religious phenomenon on the horizon, would be more aware of the nascent group called Christianity than of its putative founder Jesus. Some of these writers, at least, had had direct or indirect contact with Christians; none of them had had contact with the Christ Christians worshiped. This simply reminds us that Jesus was a marginal Jew leading a marginal movement in a marginal province of a vast Roman Empire. The wonder is that any learned Jew or pagan would have known or referred to him at all in the 1st or early 2d century. Surprisingly, there are a number of possible references to Jesus, though most are riddled with problems of authenticity and interpretation. The first and most important potential “witness” to Jesus life and activity is the Jewish aristocrat, politician, soldier, turncoat, and historian, Joseph ben Matthias (A.D. 37 /3 8-sometime after lOa). Known as Flavius Josephus from his patrons the Flavian emperors (Vespasian and his sons Titus and Domitian), he wrote two great works: The Jewish war, begun in the years immediately following the fall of Jerusalem in A.D. 70, and the much longer Jewish Antiquities, written ca. 93-94. Both books, at least in some versions, contain passages mentioning Jesus. The problem is that at least one passage is certainly a later Christian product. The question is: Are the other passages spurious as well?

The clearly unauthentic text is a long interpolation found only in the Old Russian (popularly known as the “Slavonic”) version of The jewish War, surviving in Russian and Rumanian manuscripts.” This passage is a wildly garbled condensation of various Gospel events, seasoned with the sort of bizarre legendary expansions found in apocryphal gospels and acts of the 2d and 3d centuries. Despite the spirited and ingenious attempt of Robert Eisler to defend the authenticity of much of the Jesus material in the Slavonic jewish m.r, almost all critics today discount his theory. In more recent decades, G. A. Williamson stood in a hopeless minority when he tried to maintain the authenticity of this and similar interpolations, which obviously come from a Christian hand (though not necessarily an orthodox one). More difficult to judge are the two references to Jesus in The jewish Antiquities. The shorter passage-and the one less disputed–{)ccurs in a context where Josephus has just described the death of the procurator Festus and the appointment of Albinus as his successor (A.n. 62). While Albinus is still on his way to Palestine, the high priest Ananus the Younger convenes the Sanhedrin without the procurators consent and has certain enemies put to death. The key passage (Ant. 20.9.1 §200) reads: “Being therefore this kind of person [i.e., a heartless Sadduceel, Ananus, thinking that he had a favorable opportunity because Festus had died and Albinus was still on his way, called a meeting [literally, “sanhedrin”l of judges and brought into it the brother of Jesus-who-iscalled-Messiah [ton adelphon leSOU tou legomenou Christoul, James by name, and some others. He made the accusation that they had transgressed the law, and he handed them over to be stoned.” There are a number of intriguing points about this short passage. First of all, unlike the text about Jesus from the Slavonic Josephus, this narrative is found in the main Greek-manuscript tradition of The Antiquities without any notable variation. The early 4th-century Church historian Eusebius also quotes this passage from Josephus in his Ecclesiastical History (2.23.22). Second, unlike the extensive review of Jesus ministry in the Slavonic Josephus, we have here only a passing, almost blase reference to someone called James, whom Josephus obviously considers a minor character. He is mentioned only because his illegal execution causes Ananus to be deposed. But since “James” (actually, the Greek form of the English name James is [allobas, Jacob) is so common in Jewish usage and in Josephus writings, Josephus needs some designation to specify which Jacob/James he is talking about. Josephus apparently knows of no pedigree (e.g., “James the son of Joseph”) he can use to identify this James; hence he is forced to identify him by his better-known brother, Jesus, who in turn is specified as that particular Jesus “who-is-calledMessiah.” This leads to a third significant point: the way the text identifies James is not likely to have come from a Christian hand or even a Christian sonrce. Neither the NT nor early Christian writers spoke of James of Jerusalem in a matter-of-fact way as “the brother of Jesus” (ho adelphos lesoo), but rather-with the reverence we would expect-“the brother of the Lord” (ho adelphos tou kyriou) or “the brother of the Savior” (ho adelphos tou roferos). Paul, who was not overly fond of James, calls him “the brother of the Lord” in Gall: 19 and no doubt is thinking especially of him when he speaks of “the brothers of the Lord” in 1 Cor 9:5. Hegesippus, the Zd-century Church historian who was a Jewish convert and probably hailed from Palestine, likewise speaks of “James, the brother of the Lord” (in Eusebius Ecclesiastical History 2.23.4); indeed, Hegesippus also speaks of certain other well-known Palestinian Christians as “a cousin of the Lord” (4.22.4), “the brothers of the Savior” (3.32.5), and “his [the Lords] brother according to the flesh” (3.20.1). The point of all this is that Josephus designation of James as “the brother of Jesus” squares neither with NT nor with early patristic usage, and so does not likely come from the hand of a Christian interpolator. Fourth, the likelihond of the text coming from Josephus and not an early Christian is increased by the fact that Josephus account of jamess martyrdom differs in time and manner from that of Hegesippus. Josephus has James stoned to death by order of the high priest Ananus before the Jewish War actually breaks out (therefore, early in A.D. 62). According to Hegesippus, the scribes and Pharisees cast James down from the battlement of the Jerusalem temple. They begin to stone him but are constrained by a priest; finally a laundryman clubs James to death (2.23.12-18). jamess marryrdom, says Hegesippus, was followed immediately by Vespasians siege of Jerusalem (A.D. 70). Eusebius stresses that Hegesippus account agrees basically with that of the Church Father Clement of Alexandria (2.23.3,19); hence it was apparently the standard Christian story. Once again, it is highly unlikely that Josephus version is the result of Christian editing of The Jewish Antiquities. Fifth, there is also the glaring difference between the long, legendary, and edifying (for Christians) account from Hegesippus and the short, matter-of-fact statement of Josephus, who is interested in the illegal behavior of Ananus, not the faith and virtue of James. In fact, Josephus never tells us why James was the object of Ananus wrath, unless being the “brother of Jesus-who-is-called-Messiah” is thought to be enough of a crime. Praise of James is notably lacking; he is one victim among several, not a glorious martyr dying alone in the spotlight.” Also telling is the swipe at the “heartless” or “ruthless” Sadducees by the pro-Pharisaic Josephus; indeed, Josephus more negative view of the Sadducees is one of the notable shifts from The Jewish War that characterize The Antiquities. ” In short, it is not surprising that the great Josephus scholar Louis H. Feldman notes: ” … few have doubted the genuineness of this passage on James.”” If we judge this short passage about James to be authentic, we are already aided in the much more difficult judgment ahout the second, longer, and more disputed text inAne. 18.3.3 §63-64. This is the so-called Testimonium Flavianum (i.e., the “testimony of Flavius Josephus”). Almost every opinion imaginable has been voiced on the authenticity or inauthenticity of this passage. Four basic positions can be distilled.” (1) The entire account about Jesus is a Christian interpolation; Josephus simply did not mention Jesus in this section of The Antiquities. (2) While there are signs of heavy Christian redaction, some mention of Jesus at this point in The Antiquities-perhaps a pejorative one—-caused a Christian scribe to substitute his own positive account. The original wording as a whole has been lost, though some traces of what Josephus wrote may still be found. (3) The text before us is basically what Josephus wrote; the two or three insertions by a Christian scribe are easily isolated from the clearly non-Christian core. Often, however, scholars will proceed to make some modifications in the text after the insertions are omitted. (4) The Testimonium is entirely by Josephus. With a few exceptions, this last position has been given up today by the scholarly community. H The first opinion has its respectable defenders but does not seem to be the majority view. IS Most recent opinions move somewhere within the spectrum of the second and third positions. 16 It is perhaps symptomatic that among sustainers of some authentic substratum (plus Christian additions, changes, and deletions) are the Jewish scholars Paul Winter and Louis H. Feldman, the hardly orthodox Christian scholars S. G. F. Brandon and Morton Smith, main-line Protestant scholars like James H. Charlesworth, and Catholic scholars like Carlo M. Martini, Wolfgang Trilling, and A.-M. Dubarle.” As it stands in the Greek text of The Antiquities (the so-called “Vulgate” text), the Testimonium reads thus:

At this time there appeared18 Jesus, a wise mao, if indeed one should call him a man. For he was a doer of startling deeds, a teacher of people who receive the truth with pleasure.” And he gained a following both among many Jews and among many of Greek origin. He was the Messiah. And when Pilate, because of an accusation made by the leading men among us, condemned him to the cross, those who had loved him previously did not cease to do 50. 20 For he appeared to them on the third day, living again, just as the divine prophets had spoken of these and countless other wondrous things about him. And up until this very day the tribe of Christians, named after him, has not died out.21 At first glance, three passages within the Testimonium strike one as obviously Christian: (1) The proviso “if indeed one should call him a man” seeks to modify the previous designation of Jesus as simply a wise man. A Christian scribe would not deny that Jesus was a wise man, but would feel that label insufficient for one who was believed to be God as well as man.” Granted, as Dubarle points out,21 Josephus elsewhere uses hyperbole (including words like “divine” and “divinity”) to describe great reli~ gious men of the past; and so Dubarle prefers to retain this clause in the original text. However I I do not think the context of the Testimonium as a whole exudes the lavish laudatory tone that would cohere with such a reverent conditional clause here. 24 (2) “He was the Messiah” is clearly a Christian profession of faith (ef. Luke 23:35; John 7:26; Acts 9:22-each time with the boutos used here in Josephus, and each time in a context of Jewish unbelief}. This is something Josephus the Jew would never affirm. Moreover, the statement “He was the Messiah” seems out of place in its present position and disturbs the flow of thought. If it were present at all, one would expect it to occur immediately after either “Jesus” or “wise man,” where the further identification would make sense.” Hence, contrary to Dubarle, I consider all attempts to save the statement by expanding it to something like “he was thought to be the Messiah” to be ill advised. Such expansions, though witnessed in some of the Church fathers (notably Jerome), are simply later developments in the tradition.” Other critics have tried to retain a reference to Christos, “the Messiah,” at this point on the grounds that the title seems to be presupposed by the last part of the Testimonium, where Christians are said to be “named after him” (Le., Jesus who is called Christ). This explanation of the name Christian, it is claimed, seems to require some previous reference in the passage to the title Christ. But as Andre Pelletier points out, a study of the style of Josephus and other writers of his time shows that the presence of “Christ” is not demanded by the final statement about Christians being “named after him.” At times both Josephus and other Greco-Roman writers (e.g., Cassius Dio) consider it pedantry to mention explicitly the person after whom some other person or place is named; it would be considered an insult to the knowledge and culture of the reader to spell out a connection that is rather taken for granted.” Moreover, a glancing reference to the name Christ or Christians, without any detailed explanation, is exactly what we would expect from Josephus, who has no desire to highlight messianic figures or expectations among the Jews.” (3) The affirmation of an appearance after death (“For he appeared to them on the third day, living again, just as the divine prophets had spoken of these and countless other wondrous things about him”) is also clearly a Christian profession of faith, including a creedal “according to the Scriptures” (cf. 1 Cor 15:5).29 Dubarle seeks to save the post-mortem appearance for Josephus by rewriting the text to make this statement the object of the disciples preaching.” In my view, Dubarles reconstruction rests on a shaky foundation: he follows the “majority vote” among the various indirect witnesses to the Testimonium in the Church fathers.” In short, the first impression of what is Christian interpolation may well be the correct impression.” A second glance confirms this first impression. Precisely these three Christian passages are the clauses that interrupt the flow of what is otherwise a concise text carefully written in a fairly neutral-or even purposely ambiguous-tone: At this time there appeared Jesus, a wise man. For he was a doer of startling deeds, a teacher of people who receive the truth with pleasure. And he gained a following both among many Jews and among many of Greek origin. And when Pilate, becanse of an accusation made by the leading men among us, condemned him to the cross, those who had loved him previously did not cease to do so. And up until this very day the tribe of Christians (named after him) has not died out. The flow of thought is clear. Josephus calls Jesus by the generic title “wise man” (sophos an … , perhaps the Hebrew qiikiim). He then proceeds to “unpack” that generic designation with two of its main components in the Greco-Roman world: miracle working and effective teaching.” This double display of “wisdom” wins him a large following among both Jews and Gentiles, and presumably-though no explicit reason is given-it is this huge success that moves the leading men to accuse him before Pilatel< Despite his shameful death on the cross,” his earlier adherents do not give up their loyalty to him, and so (note the transition that is much better without the reference to the resurrection)36 the tribe of Christians has not yet died out. But even if these deletions do uncover an earlier text, is there sufficient reason to claim that it comes from Josephus? The answer is yes; our initial, intuitive hypothesis can be confirmed by further considerations drawn from the texts history, context, language, and thought. First of all, unlike the passage about Jesus in the Slavonic Jewish 1#Ir, the Testimonium is present in all the Greek manuscripts and in all the numerous manuscripts of the Latin translation, made by the school of Cassiodorus in the 6th century; variant versions in Arabic and Syriac have recently been added to the large inventory of indirect witnesses.” These facts must be balanced, however, by the sobering realization that we have only three Greek manuscripts of Book 18 of The Antiquities, the earliest of which dates from the 11th century. One must also come to terms with the strange silence about the Testimonium in the Church Fathers before Eusebius.” I will return to this point at the end of the treatment of Josephus. Second, once we have decided that the reference to “the brother of Jesus-who-is-called-Messiah, James by name” is an authentic part of the text in Book 20, some earlier reference to Jesus becomes a priori likely. Significantly, in Ant. 20.9.1 Josephus thinks that, to explain who James is, it is sufficient to relate him to “Jesus-who-is-called-Messiah.” Josephus does not feel that he must stop to explain who this Jesus is; he is presumed to be the known fixed point that helps locate James on the map. None of this would make any sense to Josephus audience, which is basically Gentile, unless Josephus had previously introduced Jesus and explained something about him.” Of course, this does not prove that the text we have isolated in Ant. 18.3.3 is the original one, but it does make probable that some reference to Jesus stood here in the authentic text of The Antiquities. Third, the vocabulary and grammar of the passage (after the clearly Christian material is removed) cohere well with Josephus style and language; the same cannot be said when the texts vocabulary and grammar are compared with that of the NT.4. Indeed, many key words and phrases in the Testimonium are either absent from the NT or are used there in an entirely different sense; in contrast, almost every word in the core of the Testimonium is found elsewhere in Josephus-in fact, most of the vocabulary turns out to be characteristic of Josephus. 41 As for what I identify as the Christian insertions, all the words in those three passages occur at least once in the NT.” One must beware of claiming too much, though. Some of the words in the interpolations occur in the NT only once, and some occur more often in Josephus. Still, the main point stands: in that part of the Testimonium which-on other grounds-seems to come from Josephus and not from a Christian, the vocabulary and style jibe well with that of Josephus,” and not quite so well with that of the NT. This distinction between the vocabulary of Josephus and the vocabulary of the NT does not hold in the three passages I identify as Christian interpolations. There, the text shows more of an affinity to NT vocabulary than does the rest of the Testimonium. This comparison of vocabulary between Josephus and the NT does not provide a neat solution to the problem of authenticity, but it does force us to ask which of two possible scenarios is more probable. Did a Christian of some unknown century so immerse himself in the vocabulary and style of Josephus that, without the aid of any modern dictionaries and concordances, he was able to (1) strip himself of the NT vocabulary with which he would naturally speak of Jesus and (2) reproduce perfectly the Greek of Josephus for most of the Testimonium-no doubt to create painstakingly an air of verisimilitude-while at the same time destroying that air with a few patently Christian affirmations? Or is it more likely that the core statement, (I) which we first isolated simply by extracting what would strike anyone at first glance as Christian affirmations, and (2) which we then found to be written in typically Josephan vocabulary that diverged from the usage of the NT, was in fact written by Josephus himself? Of the two scenarios, I find the second much more probable. These observations are bolstered by a fourth consideration, which dwells more on the content of what is said, especially its implied theological views. (1) If we bracket the three clearly Christian passages, the “christology” of the core statement is extremely low: a wise man like Solomon or Daniel who performed startling deeds like Elisha, a teacher of people who gladly receive the truth,” a man who winds up crucified, and whose only vindication is the continued love of his devoted followers after his death. Without the three Christian passages, this summary description of Jesus is conceivable in the mouth of a Jew who is not openly hostile to him, but not in the mouth of an ancient or medieval Christian. Indeed, even if we were to include the three passages I designate as Christian, the christology would still be jejune for any Christian of the patristic or medieval period, especially if, as many suppose, the Christian interpolation would have to come from the late 3d or early 4th century.45 By this time, whether one was an Arian or an “orthodox” Catholic, whether one had incipient Nestorian or Monophysite tendencies, this summary about Jesus person and work would seem hopelessly inadequate. 46 What would be the point of a Christian interpolation that would make Josephus the few affirm such an imperfect estimation of the God-man? What would a Christian scribe intend to gain by such an insertion?.ot7 (2) The implied “christology” aside, the author of the core of the Testimonium seems ignorant of certain basic material and statements in the four canonical Gospels. (a) The statement that Jesus “won over” or “gained a following among” both (men) many Jews and (de kai) many of those of Gentile origin flies in the face of the overall description of Jesus ministry in the Four Gospels and of some individual affirmations that say just the opposite. In the whole of Johns Gospel, no one clearly designated a Gentile ever interacts directly with Jesus;” the very fact that Gentiles seek to speak to Jesus is a sign to him that the hour of his passion, which alone makes a universal mission possible, is at hand (John 12:20-26). In Matthews Gospel, where a few exceptions to the rule are allowed (the centurion [Matt 8:5-13]; the Canaanite woman [15:21-28]), we find a pointedly programmatic saying in Jesus mission charge to the Twelve: “Go not to the Gentiles, and do not enter a Samaritan city; rather, go only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt 10:5-6). The few Gentiles who do come into contact with Jesus are not objects of Jesus missionary outreach; they rather come to him unbidden and humble, realizing they are out of place. For Matthew, they point forward to the universal mission, which begins only after Jesus death and resurrection (28:16–20). While Mark and Luke are not as explicit as Matthew on this point, they basically follow the same pattern: during his public ministry, Jesus does not undertake any formal mission to the Gentiles; the few who come to him do SO by way of exception. Hence the implication of the Testimonium that Jesus equally (polkJus men … pollous de kai) won a large following among both Jews and Gentiles simply contradicts the clear statements of the Gospels. Unless we want to fantasize about a Christian interpolator who is intent on inserting a summary of Jesus ministry into Josephus and who nevertheless wishes to contradict what the Gospels say about Jesus ministry, the obvious conclusion to draw is that the core of the Testimonium comes from a non-Christian hand, namely, Josephus. Understandably, Josephus simply retrojected the situation of his own day, when the original “Jews for Jesus” had gained many Gentile converts, into the time of Jesus. Naive retrojection is a common trait of Greco-Roman historians.· (b) The description of the trial and condemnation of Jesus is also curious when compared to the Four Gospels. All Four Gospels state explicit reasons why first the Jewish authorities and then Pilate (under pressure) decide that Jesus should he put to death. For the Jewish rulers, the grounds are theological: Jesus claims to be the Messiah and Son of God. For Pilate, the question is basically political: Does Jesus claim to be the king of the Jews? The grounds are explicated differently in different Gospel texts, but grounds there are. The Testimonium is strangely silent on why Jesus is put to death. It could be that Josephus simply did not know. It could be that, in keeping with his general tendency, he suppressed references to a or the Jewish Messiah. It could be that Josephus understood Jesus huge success to be sufficient grounds. Whatever the reason, the Testimonium does not reflect a Christian way of treating the question of why Jesus was condemned to death; indeed, the question simply is not raised. (c) Moreover, the treatment of the part played by the Jewish authorities does not jihe with the picture in the Gospels. Whether or not it be true that the Gospels show an increasing tendency to blame the Jews and exonerate the Romans, the Jewish authorities in the Four Gospels carry a great deal of responsibility-either by way of the formal trial(s) by the Sanhedrin in the Synoptics or by way of the Realpolitik plotting of Caiaphas and the Jerusalem authorities in JohnS Gospel even before the hearings hefore Annas and Caiaphas. Of course, a later Christian believer, reading the Four Gospels, would tend to conllate all four accounts, which would only heighten Jewish participation-something the rabid anti-Jewish polemic of many patristic writers only too gladly indulged in. All the stranger, therefore, is the quick, laconic reference in the Testimonium to the “denunciation” or “accusation” that the Jewish leaders make hefore Pilate; Pilate alone, however, is said to condemn Jesus to the cross. Not a word is said about the Jewish authorities pa …. ing any sort of sentence. Unless we are to think that some patristic or medieval Christian undertook a historical-critical investigation of the Passion Narratives of the Four Gospels and decided II la Paul Winter that behind Johns narrative lay the historical truth of a brief hearing by some Jewish official before Jesus was handed over to Pilate, this description of Jesus condemnation cannot stem from the Four Gospels-and certainly not from early Christian expansions on them, which were fiercely anti-Jewish. (3) Another curiosity in the core of the Testimonium is the concluding statement that “to this day the tribe of Christians … has not died out.” The use of phylon (tribe, nation, people) for Christians is not necessarily demeaning or pejorative. On the one hand, Josephus uses phylon elsewhere of the Jews (J w: 7.8.6 §327); on the other hand, Eusebius also uses phylon of Christians. 5• But the phrase does not stand in isolation; it is the subject of the statement that this tribe has not died out or disappeared down to Josephus day. The implication seems to be one of surprise: granted Jesus shameful end (with no new life mentioned in the core text), one is amazed to note, says Josephus, that this group of postmortem lovers is still at it and has not disappeared even in our own day (does Josephus have in the back of his mind Neros attempt to get it to disappear?). I detect in the sentence as a whole something dismissive if not hostile (though any hostility here is aimed at Christians, not Jesus): one would have thought by now that this “tribe” of lovers of a crucified man might have disappeared. This does not sound like an interpolation by a Christian of any stripe. (4) A final curiosity encompasses not the Testimonium taken by itself but the relation of the Testimonium to the longer narrative about John the Baptist in Ant. 18.5.2 §116-19, a text accepted as authentic by almost all scholars. The two passages are in no way related to each other in Josephus. The earlier, shorter passage about Jesus is placed in the context of Pontius Pilates governorship of Judea; the later, longer passage about John is placed in a context dealing with Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Galilee-Perea.” Separated by time, space, and placement in Book 18, Jesus and the Baptist (in that order!) have absolutely nothing to do with each other in the mind and narrative of Josephus. Such a presentation totally contradicts-indeed, it is the direct opposite of-the NT portrait of the Baptist, who is always treated briefly as the forerunner of the main character, Jesus. Viewed as a whole, the treatment of Jesus and John in Book 18 of The Antiquities is simply inconceivable as the work of a Christian of any period.” Finally, a definite advantage of the position I propose is its relative simplicity. Too many of the other proposals we have reviewed indulge in rewriting the Greek text, sometimes on flimsy grounds. This holds all the more for those who would rewrite Josephus to turn his statement into a hostile attack on Jesus.” In contrast, I have simply bracketed the clearly Christian statements. What is remarkable is that the text that remains–without the slightest alteration-flows smoothly,H coheres with Josephus vocabulary and style, and makes perfect sense in his mouth. A basic rule of method is that, all things being equal, the simplest explanation that also covers the largest amount of data is to be preferred.” Hence I submit that the most probable explanation of the Testimonium is that, shorn of the three obviously Christian affirmations, it is what Josephus wrote. An intriguing allied question is whence Josephus drew his information. Thackeray leaves open the possibility that in Rome Josephus had met Luke or read his work. 56 But, as we have seen, the language of the Testimonium is not markedly that of the NT. Of course, it is possible that Josephus had known some Christian Jews in Palestine before the Jewish War; it is even more likely that he had met or heard about Christians after taking up residence in Rome. Yet there is a problem with supposing that Josephus used the oral reports of Christians as a direct source. Strange to say, the Testimonium is much vaguer about the Christians than it is about Jesus. If my reconstruction is correct, while the Testimonium gives a fairly objective, brief account of Jesus career, nothing is said about the Christians belief that Jesus rose from the dead-and that, after all, was the central affirmation of faith that held the various Christian groups together during the 1st century (cf. 1 Cor 15:11). That Josephus drew directly on oral statements of Christians and yet failed to mention the one belief that differentiated them markedly from the wide range of Jewish beliefs at the time seems difficult to accept. My sense is that, paradoxically, Josephus seems to have known more about Jesus than he did about the Christians who came after him. Hence I remain doubtful about any direct oral Christian source for the Testimonium. Feldman notes that, as a ward of the Flavians, with residence and pension provided for his work, Josephus would have had easy access to the archives of provincial administrators that were kept in the imperial court at Rome.” Granted the obsessively suspicious nature of Tiberius in his later years, a desire for detailed reports from provincial governors on any trial that smacked of possible treason or revolt would not be surprising. Was there an account of Jesus trial among the records? An interesting surmise, but impossible to verify. Marrin prefers to think that Josephus recounts the common opinion he heard among the educated, “enlightened” Jews of the partially Romanized world he inhabited. J8 Finally, one cannot exclude-no more than one can prove-that, even apart from direct contact with Christian Jews, Josephus learned some basic facts about Jesus in Palestine before the outbreak of the Jewish War. In short, all opinions on the question of Josephus source remain equally possible because they remain equally unverifiable. We seem to have given much space to a relatively small passage; but it is a passage of monumental importance. In my conversations with newspaper writers and hook editors who have asked me at various times to write about the historical Jesus, almost invariahly the first question that arises is: But can you prove he existed? If I may reformulate that sweeping question into a more focused one, “Is there extrabiblical evidence in the first century A.D. for Jesus existence?” then I believe, thanks to Josephus, that the answer is yes.59 The mere existence of Jesus is already demonstrated from the neutral, passing reference in the report on Jamess death in Book 20.” The more extensive Testimonium in Book 18 shows us that Josephus was acquainted with at least a few salient facts of Jesus life.61 Independent of the Four Gospels, yet confirming their hasic presentation, a Jew writing in the year 93-94 tells us that during the rule of Pontius Pilate (the larger context of “during this time”)-therefore between A.D. 26 and 36-there appeared on the religious scene of Palestine a man named Jesus. He had the reputation for wisdom that displayed itself in miracle working and teaching. He won a large following, but (or therefore?) the Jewish leaders accused him hefore Pilate. Pilate had him crucified, but his ardent followers refused to abandon their devotion to him, despite his shameful death. Named Christians after this Jesus (who is called Christ), they continued in existence down to Josephus day. The neutral, or ambiguous, or perhaps somewhat dismissive tone of the Testimonium is probably the reason why early Christian writers (especially the apologists of the 2d century) passed over it in silence, why Origen complained that Josephus did not believe that Jesus was the Christ, and why some interpolator(s) in the late 3d century added Christian affirmations.” When we remember that we are hunting for a marginal Jew in a marginal province of the Roman Empire, it is amazing that a more prominent Jew of the 1st century, in no way connected with this marginal jews followers, should have preserved a thumbnail sketch of “Jesus-who-is-called-Messiah.” Vet practically no one is astounded or refuses to believe that in the same Book 18 of The Jewish Antiquities Josephus also chose to write a longer sketch of another marginal Jew, another peculiar religious leader in Palestine, “John surnamed the Baptist” (Ant. 18.5.2 §11~19). Fortunately for us, Josephus had more than a passing interest in marginal Jews.”

A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Volume I by John P. Meier